Vermont Life Winter 1977

Supplier of feed grains for six generations

E. T. & H. K. IDE CO.

Written and photographed by Richard W. Brown

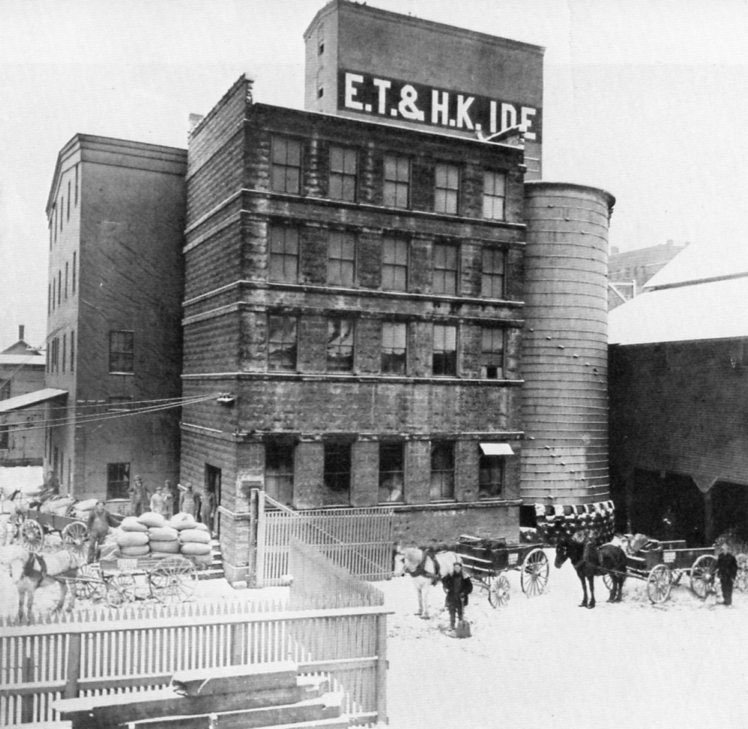

The gray, metal-sheathed grain elevator, marked by the giant letters E. T. & H. K. IDE, looms over its neighbors in the commercial district of St. Johnsbury. At seven a.m. each weekday morning, fifteen-ton trucks loaded with feed grain from this tower pull out onto Bay St. With a shifting of gears they negotiate the road that skirts the Passumpsic River, then grind their way up over the Portland St. Bridge and out into the surrounding dairy country to make deliveries to the farms strung along the dirt roads of Caledonia County. The E. T. & H. K. Ide Co. is a milling and feed business that has been the principle supplier of feed grains to the farmers of this region for six generations.

Timothy Ide owned the first mill, built in 1789 in the small village of Passumpsic, several miles downstream from St. Johnsbury. In those first years of settlement a community's very existence depended on a mill to grind the crops into grist for animal feed and bread. The Ide temperament and the miller's occupation must have suited one another, for while the original and two subsequent mills were damaged by flooding and destroyed by fire, and though the business was beset by depressions and crop shortages, Timothy Ide's great-great-great grandson now overlooks a business that has been run by a succession of Ides for 163 years. The E. T. & H. K. Ide Co. is Vermont's longest continuously running family business.

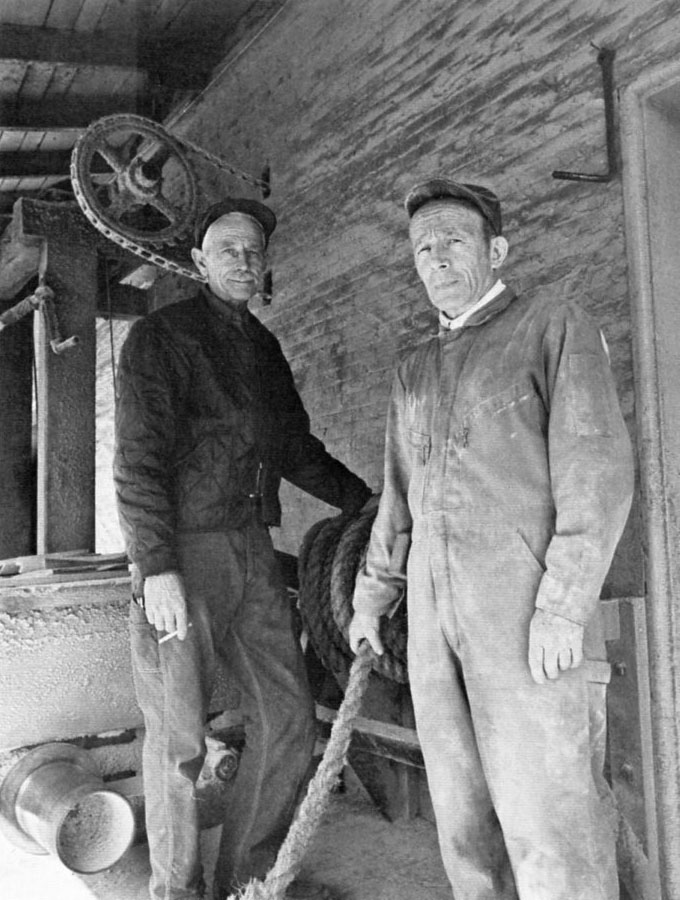

The present buildings were constructed, in 1899, on a vacant piece of marsh ground lying between the freight yards and the river at the edge of St. Johnsbury. This land was filled and graded by teams and a small army of men, and pilings were driven to solid rock to insure the stability of the construction. The mill and grain elevator were equipped with "modern" machinery—the massive mill stones and water power of the older mills were replaced by more efficient steel roller and attrition mills powered by electricity from the recently incorporated St. Johnsbury Electric Co. Today this plain, functional architecture still masks a complex maze of elevators, bins, shoots, screens, separators, dust collectors, and massive grinding machinery all used in the storing, mixing, and handling of grain. The main elevator building backs on the railroad siding. Here the hopper cars are positioned with a massive winch and unloaded with giant augers that convey the load into the building, where it is lifted to the top by a series of chain-mounted paddles and then distributed by gravity to the various storage bins below. The whole structure is rather like a giant, compartmentalized hour glass, in which the constant flow of grain measures the passage of the working day.

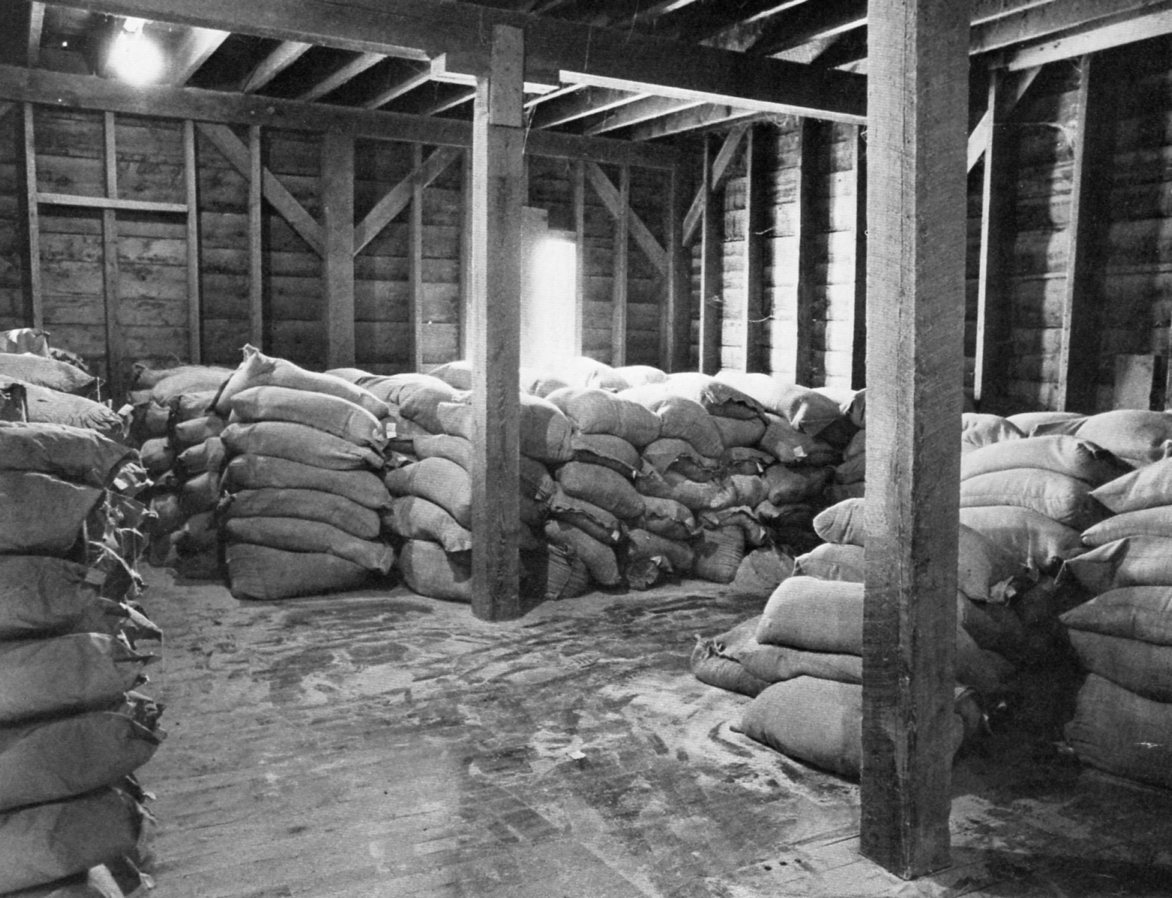

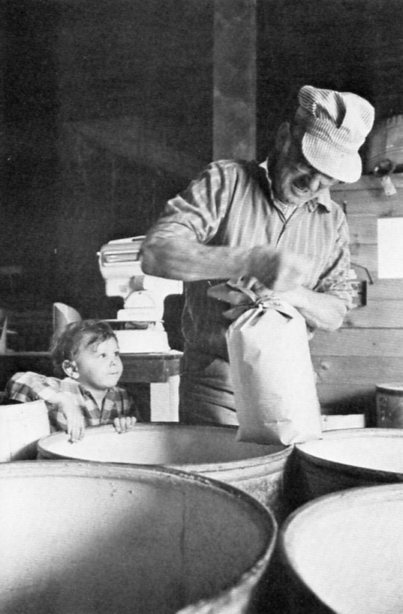

The interior of the elevator building is filled with the sounds and smells of the grain trade. In the dimly lit recesses of each floor the bags of dairy ration or beet pulp, midlings or bran lie in softly rounded stacks. Every object is coated with a layer of fragrant dust. The rich smell of molasses and oats mingles with the more exotic scent of citrus pulp from Florida which often arrives in Winter, still warm and aromatic in the bottom of the railroad car. The wood of the loading chutes and the massive supporting timbers is rubbed as smooth as a cow's stanchion by the friction of countless moving grain bags.

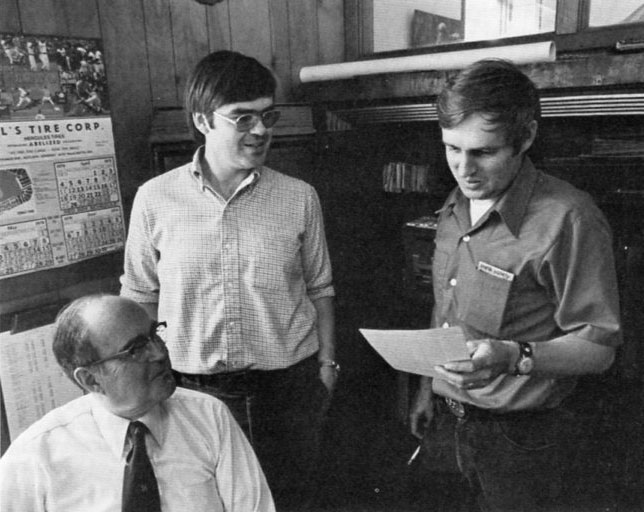

Due to changes in the economy Ide has recently become strictly a retail business and buys its grain already milled. All of the milling machinery, however, has been kept in condition and the mill still has the capability of grinding 3,000 bushels a day. Now, more than ever, dairymen in the St. Johnsbury area depend on bulk delivery of high protein feeds for adequate milk production. As Richard Ide, the present chairman, explains: "Business has actually increased, even though the number of farms has dropped. The farms have become very big with a very large usage. They're probably feeding these cows five times what they used to. Farms use up to 15 tons a week for 150 to 200 cows. When I started working, if we sold anybody 15 tons of grain this could well be the Winter's supply."

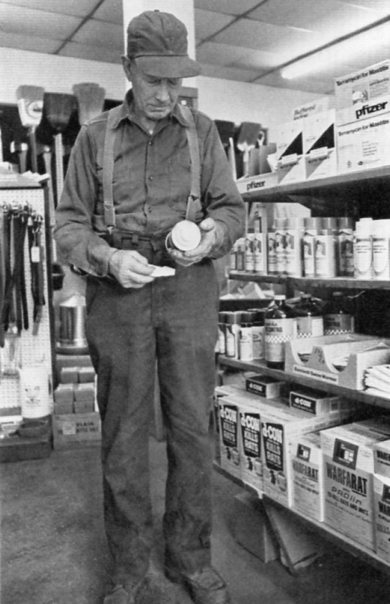

While all of the farms in this region are family farms, most are highly mechanized and the cow has become essentially a four-legged machine. Farmers also have had to increase the size of their herds in order to make an adequate living. Richard Ide recognizes the challenge these farmers face and speaks with great respect for their abilities. "The thing about farmers that's always impressed me is that this man is such a broad man. He's a cattle man, he's a crop man, he's got to be pretty clever with machinery, and he's got to be a very good financial man. So he's a pretty broad spectrum of a man. The farmer has more talents than most people, as sure as the world, he does."

With the increased recreational development of much of Vermont, and the in-viability of the small hill farm in today's economy, dairying in this state has compressed itself into a few counties in the last two decades. Fortunately for Ide, Caledonia County remains an excellent dairying region — a bit more hilly than most farmers might wish, but fertile and productive if judiciously farmed. Certainly, as long as Jerseys and Holsteins dot the surrounding hillsides, the E. T. & H. K. Ide Co. will continue to keep them well fed.

An article from the Winter 1977 edition of Vermont Life magazine.

Published 1/18/2019