To Father and Mother from Their Girls

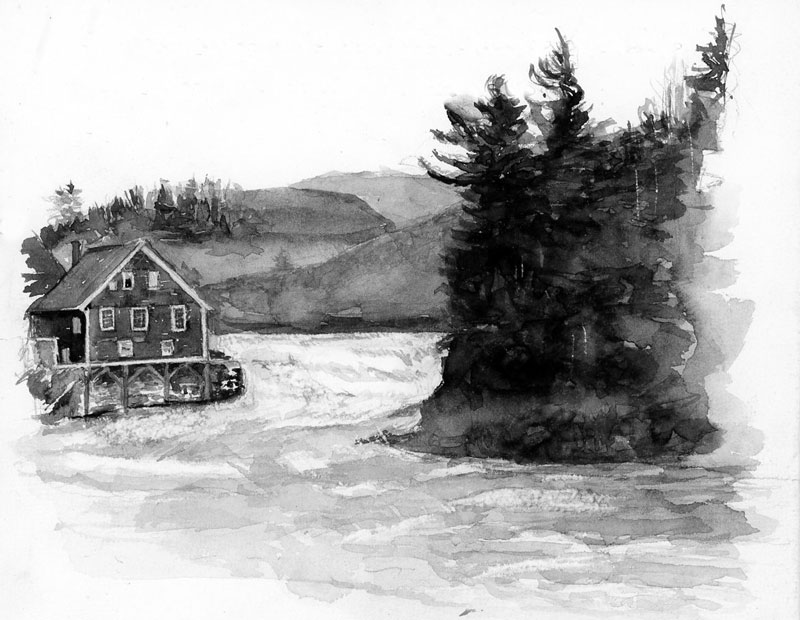

Ninety nine years ago this autumn a boy of seven walked and drove the family cows from Red Village in Lyndon to Passumpsic. His tired legs brought him slowly up Hastings Hill, past the Arnold place, which was to be woven so closely into his future, and the few scattered houses which made the village of St. Johnsbury and on to his destination, three miles below, where the river makes a fall of twenty-five feet over its rocky bed, in natural beauty and creates one of the finest water powers in the state.

For Timothy Ide, with his wife Esther Armington, had sold the farm at Red Village and bought the grist mill at Passumpsic and thus set in motion forces which would drive the family wheels and determine the family destiny for, at least a century. And it was the part of little Jacob to bring the herds into this land of promise.

Timothy was the son of John Ide and a descendent of Nicholas Ide, who came from England in 1636 and settled in Rehoboth or East Providence. John Ide was a wheelwright, a soldier and the father of a large family and in 1789 having followed faithfully the fortunes of the Revolution and thereby depleted his small savings, it seemed to him wise to join a colony of his neighbors, who were leaving Rehoboth for the purpose of taking up new land in Vermont.

And so it was that he came — with the Barkers, the Armingtons, the Wheatons, the Aldriches and the Lawrences to occupy a tract of land extending, farm adjoining farm, from the top of Crow hill in a southeasterly direction to and across the Passumpsic River and including the farm now known as the Wayside. The struggle which followed with the elements, the climate, the soil, lack of opportunity and poverty was one in which, little by little man proved himself ascendant, and out of which came men and women strong, independent, self contained and trustworthy.

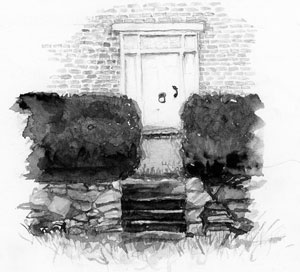

The mill which Timothy Ide bought was small and primitive in type and to it the farmers brought grain of their own raising, and in payment left a certain percentage for the own use — a toll which we hope was taken with a steady hand, a judicial eye and a regard for "Thy neighbor as thyself."

But the years rolled on and Timothy rested from the taking of toll and Jacob reigned in his stead. Jacob married Ladoska Knights who was called the prettiest girl in Waterford, and she introduced into the family a certain high spirit which was very helpful in the making of the next generation; but Grandfather once confided to me that it had always been a grief, in his secret heart, that Grandmother had not transmitted her beauty to any of her children or grandchildren. Jacob worked long and patiently and the old mill grew into one much larger and more ambitious before he passed it on to his sons, Elmore Timothy and Horace Knights who assumed control in 1860.

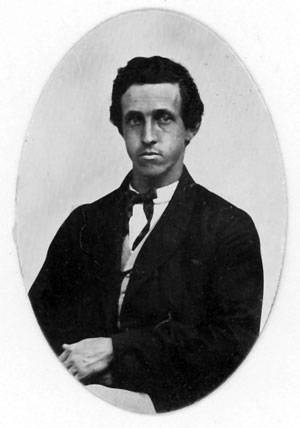

Since then mills have been twice built upon generous and progressive lines and twice burned, the business center has been changed to St. Johnsbury; but the falls are still making power which turns their wheels and grinds their grain through the intervention of electricity. The business has grown from its humble beginnings to a goodly proportion, has enlarged, expanded, developed; methods have come and gone, new conditions have been met and mastered; broad and high hopes have been realized; and into it all has been welded the daily attention, the high purpose, the strong mind of a man who has walked in integrity and, with fine judgment, builded things upon which his children look with pride. In 1860 Elmore Timothy began his business career and two years later he married Cynthia Lois Adams, a descendent of the Felches, who, in the early days, came from Wales to tame the acres which comprise the farm of Judge Steven Hastings of Waterford, and of four generations of William Adams, of old Scotch stock. Dear, big, generous, kindly Grandfather Adams! All around his eyes was a smile that ran down into his whiskers, and he knew all of the fun in the world and all about children and the things they like, and he carried some of the things in his pockets and some in his heart, and you might dig and find them all and keep them for your very own.

When we were children we used to say "Mother, what did father say when he asked you to marry him?" Now, the answer to this question was not very satisfactory; but, from what we could gather, it seemed to us that it happened something like this — Father and mother had been friends for a long time and mother was a little girl of seventeen, when father came one evening to call and was uneasy and walked up and down and at last said, "Levi and Hattie have decided to be married next week, and are going to the mountains for their honeymoon. What would you say if I should ask you to go with them and with me?" Now, Levi and Hattie were very dear friends indeed, so mother answered "Why! do you suppose I could get a dressmaker in so short a time?" And father thought she could and she did. And the drive through the mountains was a very joyous one. And then Mother always said "I am glad it was like that, children, because all the time since then has been so much nicer than all the time before."

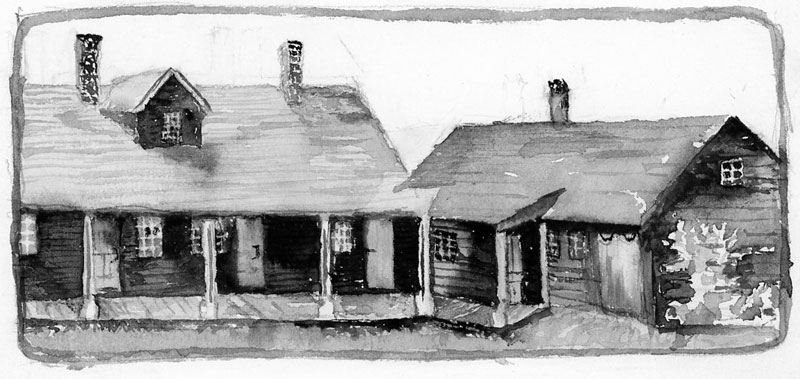

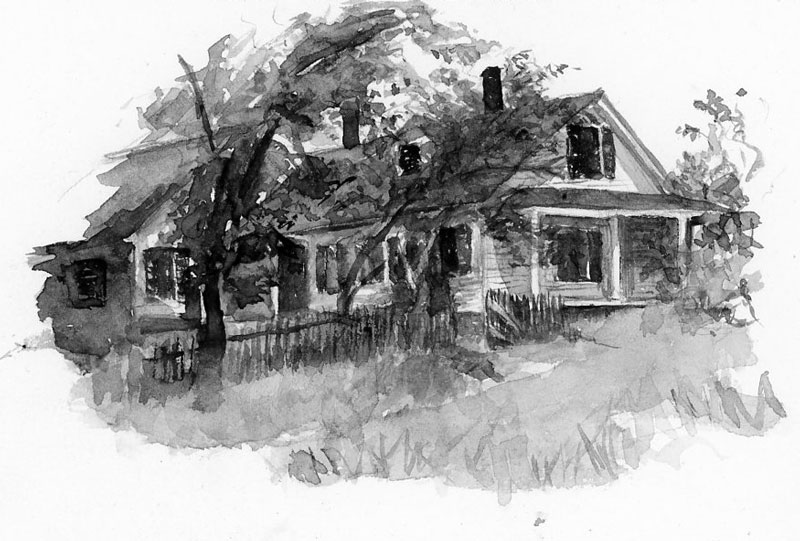

Thus it came about that there was a new home near the mill, and that in the home, was a girl wife and then a girl mother, and the dining table was made longer and longer and there were children playing in the yard and filling every nook and corner with their laughter — just jolly, wild, romping naughty little children; and nothing was too good for them to touch or too fine for them to walk upon. The house and the barns and the river and all the land was theirs; every thing had its play suggestion

and nothing was too good for them to touch or too fine for them to walk upon. The house and the barns and the river and all the land was theirs; every thing had its play suggestion and hid some enchanted fairy or some fearsome mystery. Santa Claus left nightly candy installments upon pantry shelves for children who had been almost good the day before. There were apples to be eaten, corn to be popped, stories to be told or read, and a pre-bedtime cuddle in father's arms while he sang "Old Uncle Ned" and "She fainted, o'er the table fell, and stuck her head in the butter." And O! the little sleepless midnight confessions, and the places kissed to make them well; and the mustard plasters that burned into our very souls; and and the spankings; and that awful, horror-filled dark closet, where we stayed for hours and came out in just ten minutes of the clock, convicted of sin and penitent. And, if things got a bit dull or commonplace, along came a new baby to liven them up again.

and hid some enchanted fairy or some fearsome mystery. Santa Claus left nightly candy installments upon pantry shelves for children who had been almost good the day before. There were apples to be eaten, corn to be popped, stories to be told or read, and a pre-bedtime cuddle in father's arms while he sang "Old Uncle Ned" and "She fainted, o'er the table fell, and stuck her head in the butter." And O! the little sleepless midnight confessions, and the places kissed to make them well; and the mustard plasters that burned into our very souls; and and the spankings; and that awful, horror-filled dark closet, where we stayed for hours and came out in just ten minutes of the clock, convicted of sin and penitent. And, if things got a bit dull or commonplace, along came a new baby to liven them up again.

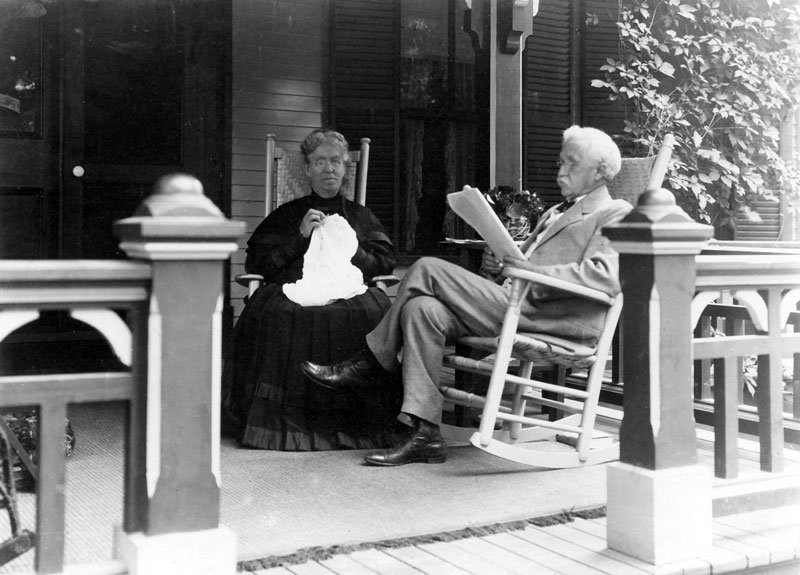

And so, on this golden wedding day, these children are happy in remembering that the business of their fathers rounds out its hundredth honorable year, and that fifty years ago two people made a home, and wove into it things that are sweet and dear-things that endure and shall endure.

A 50th anniversary gift from the daughters of Elmore and Cynthia Ide, Katherine, Mary Ellen and Fanny. Written by Katherine, lettered by Mary Ellen, and illustrated by Fanny Ide. Katherine married George Gray, Fanny married Oliver Sprague, and Mary Ellen lived at home.

Published 1/12/2019