Rob Roy and the Bloodhounds

As one grows older it is interesting to realize how often it happens that seemingly unimportant events, far in the past, become more significant than foreseen 60 years ago. In thinking back to things that became significant it is pleasant to remember some trivial things that were fun then, and still are fun.

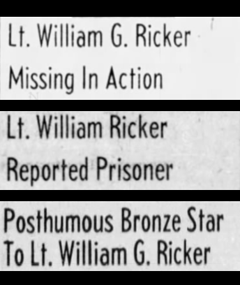

The following pages involve a number of people but specifically four boys in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, during the 1920-1940 days through grade school, the Academy and later years. Two of us have died, Bill Ricker was lost in World War II, Dick Ide died in 1979, leaving Bill Sprague and me, now in our early seventies. Someone could turn our experiences into an accurate, well-balanced document. This will be of less value and less complete for simply writing the pages, alone, without "research" and without great concern as to the order of events relating neither to importance nor proper sequence. Yet at the same time, I remember this era clearly and need little confirmation from others. So something will be gained by writing fast, and something lost by being less than studious.

For a start, why did Bill Ricker and Angus climb Mt. Washington in 1934 after dark, arriving at midnight? Why did Will Ide, Dick's father, mistrust the Academy coaches for track events, especially in running? What happened after Bill Sprague and Angus led the American History class following an hour long quiz having studied the Q. & A. booklet, on which the test was based?

As to Mt. Washington, Bill and I had been learning about 3.2% beer, soon after Prohibition was repealed in 1933. One Sunday, late afternoon in August, at Jefferson, N.H. after one bottle apiece, we were euphoric and refreshed. It became quite important to climb Mt. Washington. We sent word back to our parents 50 miles away, by some friends, thus saving money, and also prevent a flat refusal by our reasonable parents. Unfortunately our friends forgot to deliver the message. In the meantime we were well on our way. We were cautious enough to stay on the toll road, sturdy enough to go the eight miles in 4 hours and lucky enough to have clear mild weather. The Summit house at midnight was unlocked but blankets were all taken by more sensible people. It was cold, sandwiched between Mattresses, but we slept, and walked back down by sunrise, reaching St. Johnsbury by 9:30 a.m. We had learned obvious lessons, not the least being a later appreciation for our good weather that night. Such good weather was never sure for even four hours, as evidenced by small monuments of piled stone, commonly seen (in daylight) above the treeline.

It seems to me now that Mr. Will Ide, Dick's father, gave much more freedom to him than might have been expected. Dick's brother, John, had died of polio. This left only Dick as a potential heir, at age 2 or 3, to the Ide Company, founded about 100 years before Dick was born. Consciously or not, Mr. Ide may have related the nerve muscle failure in polio with "getting burned out" (his phrase) from excessive demands of track events. Hence fatigue and lowered resistance to any illness. For whatever reason, Dick spent many hours after school and traveled many miles riding his various horses during Academy days and for nearly fifty years thereafter.

About the history exam, Bill Sprague and I faced a crisis in ethics having scored #1 and #2 on a 4th year American history test. This was taught by Mr. Harold Hollister our principal and a highly respected man. Bill had found at his home a paperback listing of questions and answers for various periods during American History. For Bill to have had the best mark of the class would not have been unusual. For me to come in #2 was as unusual as for us to have stumbled onto the Q. & A. booklet in the first place. We went to Holly to tell him why we had done so well. His immediate and final answer was brief, "Boys, you are in luck."

This brings to mind another confrontation with Mr. Hollister. As seniors, Dick, Bill Ricker and Angus skipped early morning chapel - a daily and compulsory meeting. We found a warm spot facing east behind Fuller Hall. Suddenly our Principal came around the corner. There we were sitting comfortably enjoying the early June sun. He stopped for an instant, looked at us, and said, "Good morning, boys." And off he went. We realized something more than the wrong of skipping chapel. As a good man, he was kind in our wrong-doing. Nothing more was ever said.

Bill Ricker, Dick, Bill Sprague, Arland Palmer and Angus became the Rob Roy Clan. Rob Roy himself meant nothing to us. As a Scottish hero we admired him for his name, Rob Roy, and I am sure he deserved our respect. In the attic of my home, we found a secret room. It was, and still would be, worthy of something found in literature. It was 6x6x5 feet, opening up unexpectedly from a narrow space through which we crawled. Like an igloo. It was just the place to keep our documents. We had found a tin box that said "Nabisco." In this we hid our "coat of arms." That comprised of a star, an eagle and other collateral symbols. I forgot the details. All this on an 8x11 sheet of white paper. And done in red, yellow and blue ink. Most significant was the red ink we used on separate bits of paper. Each of us had signed our name. The ink had a blue tinge mixed with the red. This will happen when one uses a steel pointed pen, dug into the quick below a fingernail, to draw blood. The digging with pen, stained with ink and the subsequent red ooze was done on 6th grade time. Inserting these documents of fidelity and secrecy into the Nabisco box, by candlelight, in the Brooks' attic, made a deep impression, but not unanimously so. Arland Palmer was not long a member. In the first place he didn't enthuse about blood from such primitive, self-inflicted wounds. This to his credit. Soon another defect in character appeared. Dorothy Woods was one of the prettiest girls in our class. We felt that Arland's loyalty and close friendship to her was a threat to the secrets, written Significantly in blood, -- the secrets of the Rob Roy Clan. Looking back, Arland was on the right track. Any of us three might well have thrown the Clan aside to enjoy the attention and smiles that Dorothy shared with Arland. Anyway we couldn't allow such a friendship for him and not for all of us. We read him out. Arland was ahead of his time. My dear mother caused us to change our name from Rob Roy to a name less noble. One day at my home, en route to the attic, we passed by a meeting of my mother's friends, "Oh come in boys." She turned to her friends and said, "Let me introduce the Rob Roy Clan." So much for secrecy. We soon became "Bloodhounds." Our families all knew we were Rob Roys, but it was a revelation of sorts. Today I would like to meet the same group, sit among them and be able to give them a moment with a bagpipe.

Years ago, a St. Johnsbury man went to live in New Mexico. He was probably seeking a medical change of climate. His name was Bert Staples. Needing a new member to replace Arland, led to a link between Bert and Andrew Beck, our new candidate. Mr. Staples came to South Church every few years with some Navajo Indians. They did sand paintings on the floor, creating multi-colored designs as various sands, guided by fingers, gradually spread over a 6x4 foot area, or even larger, like a multi-colored rug. The Indians had adopted Mr. Staples. He confided to us all, in lecturing, that he had been branded by the tribe. He wished he could tell us where he was branded, but that, he said, would not be appropriate. At a later time we felt Andy Beck should become a Bloodhound and that he should be branded like Bert Staples. If not the same place, at least a brand. We picked his forearm. Having read that cold and hot were sensations subject to the power of suggestion, we blindfolded Andy. "This will burn for only a moment. Are you ready." Andy was ready and we touched him with a piece of ice. No reaction. We pressed harder. We lost the moment. Andy said, "That's cold." He was wet too. No smoke, no odor. Instantly we knew what to do. Leaving Andy blindfolded in the Ricker's garage we soon reappeared with a poker from the kitchen stove. Leaving the stove, the tip was glowing red. It cooled on route, but when Andy said he was ready, once more, we were rewarded with a quick hissing sound and a quicker cry from Andy. "That's hot." We were pleased for ourselves and pleased that, unlike Bert Staples, Andy was burned on his arm and might proudly say, "I'm a branded Bloodhound." By some paradox none of us charter members were branded. And yet Andy had never dug below his fingernails with a dirty steel pen; never signed in blood his undying devotion to Rob Roy.

Berton I. Staples came west from Vermont in 1926 and built a trading post. "With no thought at all to the locality’s past names, but with a Vermonter’s admiring nod to the man then in the White House, Staples named the place Coolidge."

Looking back, our entertainment was active and quite original, in contrast to more passive T.V. and movies today. I did see a extravaganza movie called "Way Down East" played at the Colonial Theatre. At some mid-point the lights came on. The film stopped. A man appeared on stage, "We smell smoke in the cellar. Please leave quietly. There is no danger." Or words to that effect. I was with my parents and urged them to hurry. It all turned out well. Later by months, or a very few years it did burn one night, and was replaced by the Colonial Apartments. Significantly perhaps the remnants of the original Bloodhounds were involved in creating fear, anger and annoyance at the Apartments. We ignited acetylene early one morning, at 5 a.m., outside the Colonial. Unlike the orderly exit during the "Down East" episode, we Hounds fled down Church Street fearing pursuit by apartment dwellers who might have rushed out, flowing with adrenalin. More about this later.

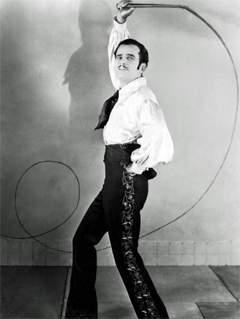

Hollywood did affect us. We went through a period of carrying long whips made of rawhide, braided and tapered, measuring 6-8 feet in length. Douglas Fairbanks could take a gun right out of the bad man's hand. Or a cigarette from the dude's mouth. Fairbanks could flash the whip and the next moment be climbing up to Mary Pickford's balcony. It seemed like quite a stunt and we were more interested in how the whip locked itself around the railing than what he and Mary had in mind.

Before or after the whips came hoops. Made of iron, about three feet in diameter and 1/2 inch thick, we took them wherever we went - wherever a smooth road or sidewalk allowed. We kept them going by beating and guiding with a short stick. Like a bicycle they required a minimum speed - somewhat faster than walking and slower than running. Some fellows guided them with a short iron rod one end of which was curled around the hoop, permanently. A variation of the hoop were old tires from the Rickers open touring automobile. Car wheels were larger then and we were smaller. Any worthy little Bloodhound could get into the tire. Today it would be called the fetal position and, pushed from behind, off we went, down a small grade - or steered down a longer grade and out of control, to the delight of one's friends.

Similar concern was shown for each other when we were old enough to ski behind the car. One day with Dick and Bill in the car with Angus hanging onto the rope at 30 m.p.h., they spotted a chunk of snow and ice lying ahead. It slid under the car, barely, and with no warning, down I went. They were as delighted as I would have been had one of them been at the end of such a rope. Once the car, a Model A Ford, slid suddenly off the road, and the skier, Brooks, went sliding past by inches. It is true to say that young boys and girls have no sense of their own value to their parents. Or no realization of their potential worth as adults.

Getting back to games, we had an ongoing love of sling shots. Once as grade school kids we got into the Chapel at the Academy. Zeus and some goddess (Athena?) made of stone got peppered pretty good. We gave them a sporting chance. They were life size head and shoulders and we stayed away by 50 feet. The pebbles made a nice sounding ping. How thoughtless of an individual to do this. How thoughtful and fun to do as a group of young boys. Speaking of sling shots, we made one on Boynton Hill. A fence of two parallel iron pipes 1 1/2 feet apart and 2 inches thick protected cars and people from a steep embankment, dropping 200 feet down to a street below called Sand Hill. Using rubber from inner tubes and hitched on the top and bottom rail we could shoot rocks of golf ball size out between the upper and lower rail. We hit a house far below on Sand Hill. Nearby in dense woods we had many trails. At a strategic point the main trail split into 3-4 little trails. We knew from previous plans that in case of emergency we were to run for the main trail. At the shout of "S" we could separate, each to his own smaller trail. When the rock hit the roof far below, we abandoned the fence with its telltale evidence, and raced for refuge shouting "S,S,S." Nothing like being well drilled for such emergencies.

Dr. Ricker, Arthur Sprague, Joe Brooks and Will Ide all saw the need of an extra year of learning for these former Bloodhounds. Dick to Beacon School near Boston before returning home to E.T. & H.K. Ide. Bill Sprague was off to Exeter. Angus and Bill Ricker went to Deerfield. None of us knew where this would lead as to college or later careers. Dick had been given a choice of college, an equivalent experience of world travel or returning after Beacon School to the family business.

Speaking of polio, an epidemic in the Connecticut Valley gave Bill Ricker and me 10 days of camping at Caspian Lake, during late September of 1931. Deerfield postponed opening until cooler weather in October. Cold weather did act like a temporary vaccine against polio, for whatever reason. Using the Rickers' World War I army camping gear, we pitched our tents near Greensboro Village on the shore of Caspian Lake. The millstream for Barringtons Grain Mill, now a gift shop, flowed out of Caspian a few feet from our tent. With a week of fine weather, we golfed 27 holes a day, walked back the mile down into Greensboro and bought meat, milk, bread and potatoes for the big meal. By dark by the fire supper was done and we anticipated one of our new-found pleasures. Later it would have been cigarettes and later still it was beer, as noted above. Between the Village and the Lake (200 yards) was a small field of corn. We stole by dusk - not corn - but cornsilk. With our pipes, aglow with cornsilk, we had the world by a string. And best of all we knew how lucky we were. None of our families suffered outwardly from the depression. There must have been hardship in Vermont as with the nation.  We were less aware of it because Vermont was rural and because we didn't see it for the national disaster that it was. Some school friends disappeared as parents looked for new employment. Some otherwise would have stayed in town. Who were they? Compared to whom? What would have happened differently were things prosperous? No basis for knowing then or even less so now. We were healthy fortunate boys in caring families who were willing and able to send us away. Before leaving this, and to get back for a moment to the glories of cornsilk, I have since, as a pipe and tobacco man, gone back experimentally to cornsilk. Also tea, coffee and pine needles. Speaking of burn-out, I found these products were bitter and hot. Years ago Old Gold cigarettes claimed "Not a cough in a carload." Dry pine needles rolled into a cigarette not only made us cough, our fingers were also at risk. At best, people never became addicted to those flammable products.

We were less aware of it because Vermont was rural and because we didn't see it for the national disaster that it was. Some school friends disappeared as parents looked for new employment. Some otherwise would have stayed in town. Who were they? Compared to whom? What would have happened differently were things prosperous? No basis for knowing then or even less so now. We were healthy fortunate boys in caring families who were willing and able to send us away. Before leaving this, and to get back for a moment to the glories of cornsilk, I have since, as a pipe and tobacco man, gone back experimentally to cornsilk. Also tea, coffee and pine needles. Speaking of burn-out, I found these products were bitter and hot. Years ago Old Gold cigarettes claimed "Not a cough in a carload." Dry pine needles rolled into a cigarette not only made us cough, our fingers were also at risk. At best, people never became addicted to those flammable products.

Speaking of flames, and the pressure of peers, recalls an irresponsible thing that two of us did. We were hiking in late spring 3-4 miles north of town in fields and woods. We ate sandwiches at noon, lolled around and then got ready to leave for home. Suddenly we were responsible for a small fire, spreading faster than we could stamp out with our boots. We were near woods. One of us pulled off his knapsack, took off his wool jacket and together we beat out a six foot circle of flames. All of us are sometimes careless about smoking in the woods. Sure, but we set this fire, not once but three times. The first two we could control by stamping them out. So we tried the third time. What kind of thinking is this. May it not be an urge, in boys especially, to be free of restraints even while living in homes that gave us considerable freedom and with it the freedom to abuse our freedom. It wasn't all due to peer pressure. Once while alone in our cellar at home I had a very shocking experience. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing as I learned after removing the bulb from a ceiling outlet. What would possess anyone to stick the iron poker into the open socket??? None of us were that rebellious. If it were true then that "Curiosity killed a cat. Satisfaction brought him back," if that was true it gave me so little satisfaction or pride that I told no one about it. And then only after being out in the world, known as a fairly responsible and conservative citizen. Least of all it was never shared with my fellow Bloodhounds. Speaking parenthetically of Bloodhounds for a moment, comes an extraneous thought. Did we become Bloodhounds instead of Terriers, Retrievers, or Bulldogs, because of our signatures inside the Nabisco box?

At the expense of prolonging this too far, and jumping about too much at random, I do want to get back to acetylene and the Colonial Apartments.

In grade school we read "Boys Life" and "American Boy," weekly or monthly magazines, best remembered for exotic ads. Exotic is the wrong word, but Big Bang pistols and cannons were exciting. The pistols were actually about life size and the cannons were about a foot long with red wheels and perhaps a 1 inch bore. A mix of calcium and carbon when mixed with water forms flammable acetylene, a cousin of propane, and like propane, in our stoves, can burn or explode. We were interested in the latter. The cannon (Big Bang) allowed one to measure out accurately a few granules of carbide, insert it into the breech, where mixed with water, already in place, formed acetylene. Pulling the trigger by a yard long string threw a spark from flint, and we were rewarded as the little cannon jumped back 1/2 inch. Smoke and a tiny flame added to our joy. We outgrew this toy, but later, Dick and Bill Ricker, exposed to physics and chemistry as sophomores, remembered Big Bang. The final result ready for the 4th of July was a much bigger bang, starting with an old hitching post 5 feet long of cast iron, with a bore of 3-4 inches. We mounted it on a four wheeled cart called a Sherwin Spring Coaster. The cart wheels were 5-6 inches and each wheel actually had a small coiled spring. Quite advanced it was and while large enough to carry the cannon at an angle of 45 degrees, it was at the same time so small that the cannon's mouth extended beyond the cart, as any good cannon should. We plugged the lower end with a baseball. Dick and Bill bored a hole near the baseball, inserted a spark plug, arranged a switch and battery. We were ready. And mobile. Ready for what? How much charge of carbide, like how much gun powder say would any home made cannon need? We worried about too little and not about too much. Without continuing scientifically by using small quantities of calcium carbide, we put "enough" into the palm of our hand and threw it down the bore, to the breech, near the water and the baseball. We stood a long way off before throwing the switch. Like 3 feet. We soon found out about whether the charge was too little or too much. Fire belched 2-3 inches from the cannon's mouth. The roar was impressive. The cart recoiled 4-5 inches! The charge was perfect. The volume of water and the palm of carbide crystals was just right. Mr. Ranger in chemistry would have said q.s.- quantum satis.

Without further detail you can guess what we were doing at 5 a.m. near the doors of the Colonial Apartments. It had been a hot night. Windows were open. An interesting matter of acoustics relates, nearly 60 years later, to the U-shaped courtyard into which we fired. Across the street, 100 feet away stands the massive masonry of North Church. We didn't actually hear an echo, but it was the loudest explosion we had yet attained. We heard groans and one articulate oath. So out poured our own adrenalin and off down Church Street we ran, glad of the mobility of our cannon, as well as our own young legs. Actually we weren't that young. We were old enough to have at least thought of the cast iron hitching post blowing up in our faces. And also socially old enough to know the difference between a prank which could be fun for all, and something that becomes almost malicious. Or were we? Looking back, we were close to trouble. We escaped physically and socially. Nevertheless, thank you Big Bang Cannon, so attractively shown, on small scale in Boy's Life.

Church played a role in our lives. I feel we learned more by example in our homes than by moral edicts in either home or church, during those years. One cannot speak for others, however. Someone has made the analogy of ploughing ground that may never be planted or harvested. Going to church is something we ploughed without great inspiration. Later, and now much later, church has been important. I remember being reduced to tears in church at age 7 or 8. A man who climbed the face of buildings - The Human Fly - started up the Avenue Hotel. Especially I remember how when reaching the overhang of the flat roof he dangled holding on by his hands trying to get his feet somehow above his hands. He began to swing like a pendulum, almost able to get one foot up to roof level. Next morning, Mr. DeLapp, our pastor, asked how many of us had seen the Human Fly. Many had, but only Angus raised his hand. I began to cry. The Human Fly had succeeded. He made it. Somehow I had failed, for when mine was the only hand raised, people laughed. Mr. DeLapp could have saved me but I was left dangling. My Dad never cared too much for Mr. DeLapp. He said that a pastor should use the word that sounded to me like "frinstance." Another time in a church without envelopes for the offering, people put in loose change and could also make change. My Dad passed the plate along to me. Quite a bit heavier than expected. Money all over the place, bouncing off the wooden floor. My kingdom for a rug. So if we boys were ploughing, there were sometimes rocks in the field. Arland, Bill, Dick and Bill all went to the North Church. For that reason I asked if we could change from South to North. Denied, as it should have been. However, every fall there were Sunday evening meetings for young people, called "the School of Missions." It brought us together for 9 weeks involving boys and girls of the Methodist, the North and the South Churches. Lessons were followed by cocoa and sandwiches and then a skit of some sort. I remember we were impressed by Bill Ricker. He had more imagination than we. Later in the Academy he joined the dramatic club. Also he dared to date Phyllis Phillips who was much older than any of us and also one of the brightest and prettiest. She was, furthermore, the daughter of George Phillips the greatly loved and respected minister at the Methodist Church. Phyllis was older by one class at the Academy, and Bill broke right through that barrier. Anyway, a few years earlier, back at the School of Missions, Bill, dressed as an Arabian, called loudly, "Alla Hak Abba." I think now it meant, "God be praised." At the time we probably smiled and said "Atta Boy Bill."

Speaking of drama and the stage, Bill and I played trombones in the Academy orchestra. Bill Sprague was a good pianist. One year we all worked on the Hungarian Rhapsody #2. Later at the Vermont Music Festival, many schools joined forces on the Rhapsody and never did our trombones sound better. Like singing well in chapel. Three hundred voices led by Annie P. Stevenson asking "Do you ken John Peel with his coat so gray? Do you ken John Peel at the break of day?" We could belt it out, knowing one's own voice was sounding pretty good. As with our trombones at the Vermont Festival in Burlington we were supported by many others. However a trombone duet by Bill and me one day in chapel was something else. It was to be "The Bells of St. Mary's." I had the melody and Bill had the bass. A few days ahead of the big day, our guru, Mr. Donovan, director of the Rotary Boys Band, suggested that Bill do the lead because it was apparent to him - he felt it would go better, let us say. And I agreed, glad to get into a secondary role. I had never been close to becoming an Arabian or daring to be in the Dramatic Club. All went well for a few notes. Than we got lost. We may have swapped back to the original plan. We floundered. We began to laugh, but the show must go on. We should have quit gracefully. We couldn't stop laughing. The Bells of St. Mary's rang less and less convincingly. Loose lips are bad but they are worse when laughing into one end of a trombone. We kept laughing and strange things came out the other end. We left the stage far from gracefully - with no grace at all. Again, either one of us could have done it fairly well. As a group of two, however, we led each other astray. This happened nearly 50 years ago. My good wife, Katie, was there. She remembers this musical disaster. Someone called it a grubby performance. The dictionary says that grubby means "dirty, unkempt, infested with grubs, contemptible and beggarly." - Sitting here with her now I asked, "Was that duet a grubby thing?" hoping that it wasn't. Without hesitation she answered, "Yes. It was very grubby." Unfortunately she was also at that music festival as part of a state-wide chorus. I mean unfortunately now, because she remembers another thing. "You boys were supposed to come to take us girls out after the concert that night." We obviously didn't. Grubby again.

These few boys who enjoyed working and playing together became members of larger and wider groups. Dick earned an enviable reputation as a local and statewide businessman with E.T. & H.K. Ide in St. Johnsbury. Bill Sprague graduated from law school after Harvard. He joined his uncle's firm in Hartford. He is the senior man now in that same office, the oldest continuous firm in New England. Bill Ricker's fast growing career at W.D.E.V. in Waterbury was interrupted and then lost altogether in World War II. Arland had lost his father even before Rob Roy days. He was perhaps maturing faster than any of us, left alone as he was with his mother and sister Marguerite. How heedless and unkind children can be. Looking back now, he needed whatever of extra security a little club could offer. It was rewarding to meet him again, a few years ago, as the executive director of the United Fund or the Chamber of Commerce (or both) in Burlington.

Knowing Dick as an eligible, young, unmarried man and my knowing Margaret Pearl well enough to appreciate her character and good humor, I could see them as a great couple. When Bill Ricker married Mary Phillips in Montpelier one fine day, and once again being bold and euphoric (champagne, not beer) I suggested to Dick after the wedding that Margaret would make someone a fine wife - in fact, she ought to be his wife. Such bold matchmaking succeeded so well I never attempted it again - quitting while ahead.

My wife Kay and I, classmates of Arland, Dick and Bill were able to spend time with Margie and Dick while he gradually died in Danville. I was retired, and through the years Kay and Margie had become more like sisters than just wives of old boyhood friends. More needs to be said of this later.

During Academy days there grew a friendship between the Spragues, Twomblys (Kay's family), and the Brookses, this included my brother, Sam and my sister, Mary. It included Bill's brothers Dick and Arthur Sprague and five Twombly boys and girls. Kay's home was a meeting place. Her parents were a good influence on all of us. Many hikes started in groups from Harvey Street. Hare and hound chases went up to the "Knob" and to "Saddleback", small hills, but requiring miles of walking. On some rainy days we would be inside playing Battleship, or reading aloud. We sank fleets with pencil and paper. We read Dickens, especially Pickwick Papers. When Kay and I were alone for many summer evenings during college years, we would take food and a German grammar book, off into the hills. We enjoyed being alone! We were referred to by this larger group as Mr. and Mrs. Picknick. On these outings we didn't read Dickens. Nor did we open the German book. Later came our friendship with Bill and Julie Sprague, which still continues. Our son David went to a Camp Pinnacle, in N.H. We were pleased with his growth under strong counselors. Two of the best were Dick Sprague and his wife Marjorie. Camp was good for David and perhaps they talked about some things that I am remembering now. By chance our daughter Peggy had previously found strong leadership at Thetford, VT, at Camp Farnsworth. Dick and Marjorie Sprague - who else?

My mother served on the school board with Dr. Ricker, among others. We boys were in and out of the Ricker's house. We looked up to Nate, Margaret, and Lib. Libby and Sam Brooks "went together" during Academy days. Dr. Ricker took out all the young Brooks' tonsils at our home one morning. At medical school, much later, our dignified and respected dean, while visiting briefly with me, told how he and Rick "played poker at Yale when five dollars was five dollars."

Mr. Ide was more of a woodsman than others. Once on Burke Mt., he taught me about firing a shotgun. He thought I already knew enough not to take it, as he handed it to me - take it with my finger on the trigger. It was pointed into the woods. No harm really, but the noise was greater than Big Bang by far. And less fun. Although the gun landed on the ground he was very patient. Dick's sister Elizabeth who was older, impressed us early maturing Bloodhounds in ways we could not even express. She was beautiful and I remember glancing at her from a distance, across Main Street. Near enough to notice, but distant enough to avoid having to say anything as complicated as even "hello". She married Stanley Osborne. Sometimes he would join us at touch football on the Sprague's lawn. He had the white H woven into his red varsity sweater from Harvard. We all hoped to play well when he was there.

Dick's mother, Bill Ricker's mother and mine all died, within a span of 11-12 years at our ages of about 11, 18 and 21 respectively. Arthur and Bessie Sprague lived long lives. Their home was always a pleasant place to visit during early school days and later on. My father was alone for 24 years during which time he always gave me quiet support as he had from childhood, many times not noticed then, - but very appreciated now.

At the expense of getting out of sequence again, and looking back to the early days, Bill Sprague was the most studious of our group. He was reading Thackery and Fielding while we were perhaps discovering Mark Twain. (My favorite before Academy days was Victor Appleton who wrote the Tom Swift series. In "Tom Swift and His Submarine," I remember that, with the sub stuck in a mudbank, his giant helper Koko tore a huge battery loose from its bolts. The sub rolled free. Never mind any further need for cables, wires and power. Koko had saved Tom. A very close call.) Bill Sprague played the piano early on, and later the clarinet. While he was learning the piano Dick, Bill Ricker and I might have been "playing fireman." This meant racing our bikes out of the Ricker's garage to reach a fire. We had sirens that were powered by a small wheel in contact with the front tire as needed. The point being that Dick was the first to question the fantasy of it all, reminding us in spite of the siren that there wasn't any fire. He put away childish things, as did Bill Sprague, sooner than Bill Ricker and I did. As caddies at the country club we gradually became golfers. This was perhaps a transition from children's games to the adult world, albeit still a game. Dick grew into the grain and feed business by way of the E.T. and H.K. Ide Company stores, outside St. Johnsbury. Bill Sprague joined C.M.T.C. (Citizens Military Training Corps.) and spent some weeks at Camp Ethan Allen, near Burlington. Later he spent many summer months as a camp counselor for children.

Coming back from our early morning hike down Mt. Washington Bill Ricker was late to work, selling Singer sewing machines, where he was, like Dick, learning some basics of the business world. Earlier he had worked at Gleason's Grocery Store. My exposure to a more real world came later. I felt a growing sense of indebtedness during college that needed to be repaid. Not a financial thing alone, but a deeper realization that some opportunities given me needed to be justified. Medicine seemed then the only way to even things up. It need never to be the only way for anyone but for me it seemed so. I am glad now that it did. A project during comparative anatomy at Middlebury required dissecting the circulatory system of a cat. Arteries were injected with red dye - veins with blue. Following the blood vessels, sketching and writing, I once sat up all one night. It was inspiring then, and still is, to realize that a cat, any cat, had a circulatory plan evolved from hundreds of thousands of years ago - and this particular cat, at random, followed that plan, just as the book said it would. My brother Sam and sister Mary always encouraged my hopes to get to medical school. My kind father quietly backed me without comment but also without even questioning this further commitment by him.

Our religious lives needed some growth, judging from our more casual days. One of my classmates, to her credit used to take notes during the sermon each week. Unfortunately the notes consisted of a list of grammatical errors from the pulpit. It became a contest with her brother, won or lost each Sunday at the dinner table. You may easily guess who she is.

Bill Sprague was a counselor for several summers, as noted. It was church related camp. He served later on his church boards and committees in Newington, Conn., for 30 plus years. Dick was just as loyal and active during similar years in Danville. Approximately the same for Angus in Concord, although Kay no longer takes notes on the sermon. Previously we had all been in the Military. Bill Ricker sent me a letter from the southwest early during the war, before he was sent to Europe. In the letter he spoke meaningfully of God's role in the outcome of the war, from which he never returned. How I wish now the letter had been saved . His fulfilling life in Vermont was all too brief.

Getting back again to Dick's illness. Those were long, patient, downhill days for him in late 1979 at Danville. Through the years Kay and I visited St. Johnsbury and Danville many times. Frequently we spent weekends and some vacation days with Dick and Margie. Our weeks spent with them later, while he grew weaker, were both sad and rewarding. We were privileged to spend this time with them and their children. Near the end he was asked one day if he feared the future. Quickly he answered, "not a bit. Not a bit." During all these later years of friendship, he was one of the finest men I ever knew.

Recently Kay and I went to the funeral services of Bill's widow, Mary, in Montpelier. Tim Ide in Danville had called us. He planned to represent Margaret, who is in Florida. Tim's plans to attend had to be changed. In a sense perhaps, at Mary's funeral Kay and I represented some of the people and places remembered in these pages.

Later we met Bill's and Mary's children and spouses and grandchildren. We enjoyed talking with them and their cousins, and also with Bill's brother, Nate and sister, Libby. It was a very splendid hour. We talked again with sadness and with appreciation, as we had, six years ago, when many friends gathered in Danville for Dick's funeral, and as we had over 30 years ago at Bill's services in Montpelier.

These occasions are inevitable, but have prompted these notes, which nonetheless, I have enjoyed writing.

Angus Brooks

December 1985

Rambling reminisces about growing up in St. Johnsbury written by Angus Brooks in 1985.

Published 1/31/2021