Millers For Five Generations

The story of E. T. & H. K. Ide, Inc.

St. Johnsbury, Vermont

140th Anniversary

1813 – 1953

This year, 1953,

E. T. & H. K. Ide, Inc. celebrates its 140th Anniversary in the grain and milling business. It is one of the few companies in this country to have survived for so long a period … and one of the very few to have been owned and operated continuously for five generations by members of the same family.

The miller likes his work and takes pride in it. He likes the sight and feel of good grain. He can tell at a glance the quality, and if there is one kernel of damaged corn or one wild oat in a sample, he will detect it instantly. He likes the noise of the mill and his ear is attuned to it, so that he instantly notices any change in the speed. He even likes the fine white dust from the grinding. It smells good and it tastes good and gives his lungs something to work on.

William A. Ide

President, E. T. & H. K. Ide, Inc.

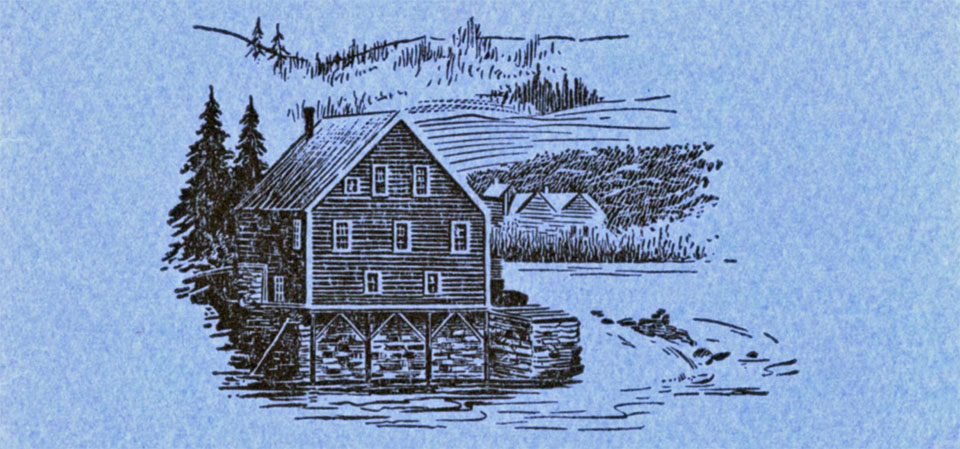

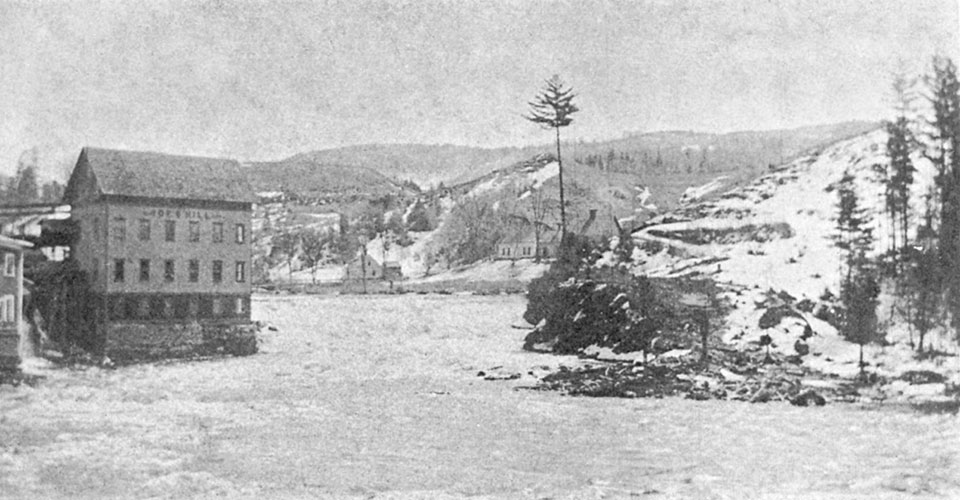

In 1813 Timothy Ide, son of John Ide, revolutionary soldier and pioneer, sold his farm in Lyndon, Vermont, and purchased the grist mill at Passumpsic, on the banks of the Passumpsic river, a few miles north of its junction with the Connecticut river.

This mill, built about 1789, was the first of several mills that have carried on a tradition of grain and milling for the Ide family through five generations and the trials and triumphs of 140 years of business.

In the early years of the nineteenth century grain and flour milling was done essentially the same way it had been done for many centuries … with water power, wooden equipment and millstones. The mill at Passumpsic was built of wood, with wooden water wheels and nearly all wooden machinery except the millstones, which were split from a granite boulder in a Vermont pasture.

These stones are still giving good service today — as doorstones. One stands at the front door of the original Ide home in Passumpsic; the other a few houses away at the former home of Frank Mason, who spent his entire working life as a miller for the Ide company

In those early days the mill did a small but steady business grinding the grain raised by nearby farmers. Corn and oats were ground for feed. Wheat was ground for flour. Practically no cash was used in the business. The miller was paid by taking a "toll" of one sixteenth of the grist. Since scales were not in use then, and the miller had to be trusted to measure his toll accurately, there were many jokes at the expense of the "honest miller."

One of these stories told of the simple-minded boy who hung around the mill and got in the way. The miller finally said to him, "Do you know anything at all?"

"Yes," said the boy, "I know the miller always has fat hogs."

"Well, well," said the miller, "so that is what you know. Tell me what you don't know."

Said the boy, "I don't know whose corn it is that fattens them."

A Friendly Business

It was impossible, however, for a miller to stay in business long without being honest. And that is still true. For even today many important transactions are carried out on the strength of the miller's word. W. A. Ide recently wrote:

The grain business is a most friendly and pleasant business. We have a personal acquaintance with most of the brokers and dealers we buy from. Some of these friendships are of many years standing and are highly valued. We also have many equally long standing and pleasant friendships with many of our customers. Controversies with buyers and sellers are rare, and are usually settled in a way that will lend to continue the pleasant relationship.

Grain is bought and sold on a constantly fluctuating market, so that purchases made at one time will show a handsome profit while those made at another time will show a depressing loss. When the words are passed between the buyer and seller by telephone — that is a trade, and no further contract is usually necessary, except a confirmation from the seller stating the grade of grain, amount bought, price, and time of shipment. According to the rules of the grain trade the acceptance of this confirmation by the buyer binds him, but legally he is not bound. What really binds him is his word, for in the grain trade a man's word must be good or he will not be in business long. When the trade is made there is no evading or cancellation by either party. If the price goes up you get the grain, and if it goes down you take it.

The Mill Stones

For many years all the grinding was done with millstones. It was not until the 1890s that the equipment was changed from stones to roller and attrition mills.

The first stones were of granite. Later buhr stones, harder and tougher than granite, were imported from France. It took skill and experience to grind with stones. The speed was regulated by opening and closing the gate to the water wheel by means of a large hand wheel near the stones. The miller had to be accurate in judging the speed of the stones and the amount of grain being fed to them, while keeping in mind the quality of the product and good capacity. The grain fed to the stones must never stop. If it did, the stones would rub together with disastrous results.

Grinding with stones was not the crude, slow process it might be thought. The flour and meal were of excellent quality, and the capacity of sharp stones was good. The greatest objection to this method was sharpening or "dressing" the stones. When they became worn or dull they had to be removed, "trued" and "picked" — long and tedious process done with a hammer-like instrument with a sharp chisel-shaped head of very hard steel. The process usually required several days and nights of work. Small particles of steel from the "pick" flew with great force and penetrated the miller's hands under the skin and stayed there so that his hands were marked with black specks forever. These were the miller's trade mark, and there was much rivalry between millers as to who "was the best hand to dress a stone."

A Man of Many Interests

From 1813 to the time of his death in 1839 Timothy Ide was a good representative of the ancient and honorable trade of miller. He reared twelve children and left them a good name and a modest business, which has been expanded by his son, his grandson, his great-grandson and his great-great grandson.

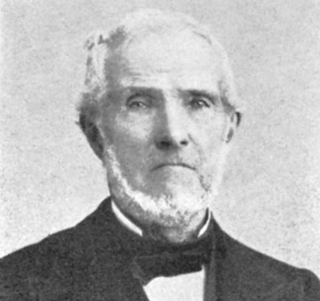

Jacob Ide, Timothy's son, became the miller in 1839. He was a man of many interests but little physical strength. For that reason he employed millers to run the mill and devoted much of his time to other pursuits. In the course of his long life he was at various times station agent and postmaster at Passumpsic, schoolmaster, storekeeper and farmer. As profitable side lines, he kept bees and raised sheep. He was successful as a mill owner because he knew he knew how to select good millers. He imported the first buhr stones and built the first elevator in this section of the country.

Jacob Ide was a quiet, thoughtful, gentle man who knew how to make men and things work for him, so that he lived a long, full and happy life. He raised three sons, each of whom achieved distinction in his own way and in his own chosen career: Elmore T. Ide as a business leader, Horace K. Ide as a soldier, and Henry Clay Ide as a lawyer and diplomat who served as Chief Justice of Samoa, Governor-General of the Philippine Islands and US Minister to Spain.

The Business Builder

Elmore Timothy Ide, Jacob Ide's eldest son, was a born miller and business man. From the time he took charge of the mill at the age of 22 in 1861, his progressive influence began to be felt. In that year the mill building and machinery were brought up-to-date and put on a more efficient operating basis.

The close of the Civil War was an important time, not only for a small business in Vermont but for the entire country. There was a restlessness in the air. New opportunities were opening up — for men who stayed at home as well as for those who went west. It was a time of birth for new enterprises and of re-birth for older businesses. It was a time for young men of vigor and courage and vision.

Elmore T. Ide was such a young man. He looked ahead and saw that the future offered rewards for a Vermont miller as well as an Oregon homesteader.

He soon found, however, that the prospect presented a challenge along with an opportunity. A new kind of flour — whiter, purer-looking "York" flour — was being brought in from the mid-west. Even though the native-ground flour was sweeter and more nutritious, as all of us know today, it could not compete with the dazzling white new stuff. Every farmer's wife wanted this new flour. Soon the farmer ceased to bring wheat to the mill to be ground. The supply of native grist wheat dwindled and nearly disappeared.

Under these conditions the mill could not he operated profitably. E. T. Ide decided he needed more knowledge of western methods and equipment. In 1865 he went "west" to Crawfordsville, Indiana, where he worked for several months as a miller and millwright. When he returned he was ready to go to work building a business in the hills of Vermont.

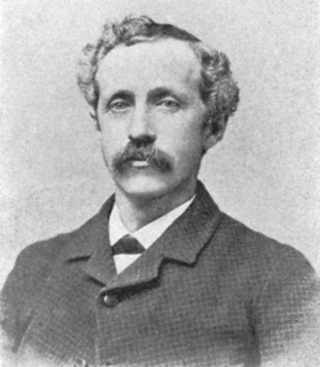

The Soldier

Meanwhile, Horace K. Ide, E. T. Ide’s brother, had returned from the Civil War with the rank of Brevet Major. He had seen four long years of hard service in the Cavalry, the last year with Custer's Division of Sheridan's Army. In addition to taking part in numerous raids and scouting expeditions, he fought in many battles with the Army of the Potomac — at Gettysburg, Yellow Tavern, Cold Harbor, Petersburg, in Sheridan's campaign in the Shenandoah Valley and in the final battles that ended at Appomattox.

Severely wounded twice, once with a 56-calibre bullet through his lungs, and nearly starved in the rebel prison at Belle Isle, he never fully recovered his health. Consequently, his participation in building the family business was limited. But his reputation as a soldier and the respect and admiration he commanded as a leader of men were important factors in the success of the business partnership of E. T. & H. K. Ide.

The Partnership

In 1866 the business was taken over by the sons, Elmore Timothy, and Horace Knights, from their father, Jacob Ide, and the partnership of E. T. & H. K. Ide was formed. The mill was again remodeled and new equipment installed for the production of white flour from western wheat. Soon the Ide mill brands of "Sea Foam", "Pearl Drop" and "Golden Sheaf" flour became popular among housewives throughout the northern section of Vermont and New Hampshire.

Like many other companies in different parts of the country at that time, this old-young company was beginning to find itself.

One year in the late 1860s the wheat crop throughout the country with the exception of California was a partial failure and of very poor quality. There was a near-famine of wheat in New England.

E. T. Ide took a bold step in buying up a large quantity of white wheat freighted by sailing vessels to New York from California. It was an experiment that paid off handsomely. For the Ide company was among the very few, if not the only mill in New England, to have a supply of this precious wheat. Ground in the mill at Passumpsic it yielded flour of the finest quality ever produced in this part of the country. Its immediate popularity greatly enhanced the growing reputation of the Ide mill.

New Headquarters

In 1869 E. T. Ide took another forward step and established a branch store in St. Johnsbury, which for many years had been steadily growing as a business and manufacturing center. This store was first located in the Ward block and later moved to 20 and 22 Eastern Avenue near the center of the business district. Horace K. Ide took charge of this branch of the business and managed it for several years until his failing health compelled him to spend most of each year in Florida.

This store did a business in both grain and groceries. In a few years it was expanded to include coal, with coal sheds and a storehouse located across the railroad tracks at the south end of the present railroad yard. Since then, supplying coal to homes and businesses in the St. Johnsbury district has continued to be an important part of the company's services.

In 1879 E. T. Ide moved his family to St. Johnsbury and established the headquarters of the business there. The mill at Passumpsic, which supplied the grain needs of the St. Johnsbury store, was left in charge of Frank Mason, a competent miller and Barnet township's most popular citizen. A large, fun-loving man with a big black moustache, universally loved and respected, Frank Mason played an important part in the success of the Ide business. Elected to the Vermont state legislature, he served one term — and could easily have been elected again and again had he been so in inclined.

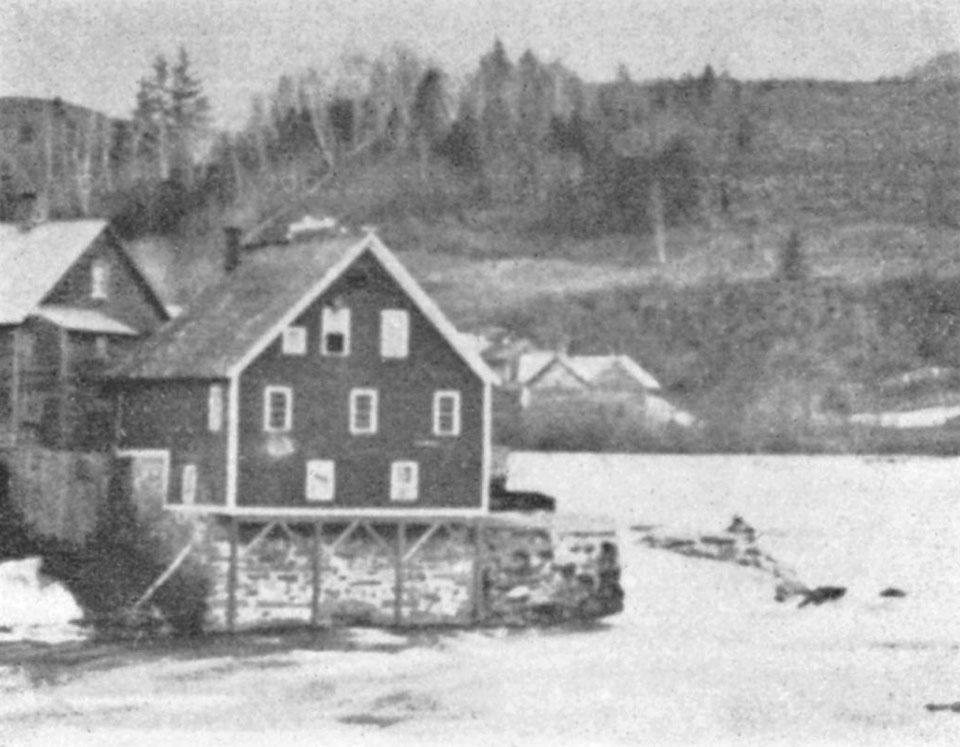

One night in the winter of 1883 fire broke out in the old mill at Passumpsic. Morning revealed a picture of complete destruction.

This fire was a heavy loss, since insurance did not begin to cover the value of the mill. The business almost came to a standstill. With H. K. Ide in Florida, E. T. Ide spent the rest of the winter making plans for the future.

Meanwhile, methods of producing flour had been changing gradually. The old mill at the time of the fire had already begun to be obsolete. Stiff competition from the big flour mills springing up in the mid-west was rapidly reducing the profit in local grinding

The partners decided that grinding grain and feed to meet the increasing demands of the farmer offered the best prospects for the future. So in the summer of 1883 an up-to-date new corn mill was built on the old site with a railroad siding leading up to its door. Large for the time, well arranged and with the height necessary for efficient elevation and handling of grain, this new mill was modern in every respect.

In 1897 H. K. Ide, long failing in health, died in New York on his way home from Florida. His death ended the partnership of E. T. & H. K. Ide, and the business was incorporated under the same name with all capital stock owned by E. T. Ide and members of his family.

The business continued to expand. In addition to doing local custom grinding the company began to buy grain in increasingly large volume from the mid-west. In the 1880s it became the first firm of its kind in this part of New England to buy western corn in carload lots. At that time this practice was considered a great risk. E. T. Ide was warned again and again that sooner or later he would be left with over-supplies of grain on hand. It proved to be so successful a risk, however, that soon the company found itself doing a substantial wholesale business, making shipments of grain of all kinds to many points in Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine.

A Venture in Real Estate

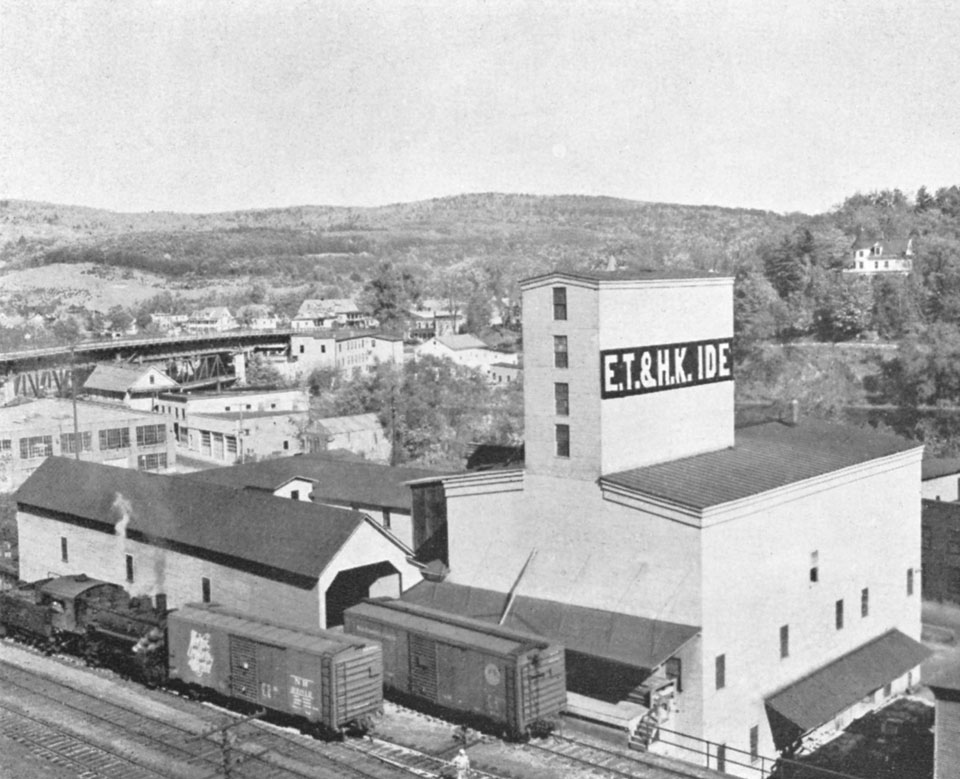

Shortly before the turn of the century E. T. Ide purchased three acres of land on the east side of the rail-road tracks in St, Johnsbury, just north of the station.

At that time this land seemed almost worthless as real estate to say nothing of its prospects as a place of business. It was virtually a swamp, in some places several feet under water, and could be reached by traffic only by constructing an underpass beneath the railroad t racks

E. T. Ide, however, saw in this unlikely swamp a new business district for St Johnsbury and set about energetically to give it value. The swamp was filled, all the filling being hauled in by horses — a laborious, time consuming job. The underpass was constructed and the street finally laid out.

Today Bay Street is an important part of the town, made so by thousands of customers who for more than fifty years have been "going out of their way" to buy grain, feed, coal and other products from E T. & H. K. Ide, Inc. For it is on this land that the main plant and offices of the company have been located since 1900.

The first part of this plant, an elevator and store house, was erected in that year. A frame building, 50 ft. by 80 ft. and five stories high with a cupola, it was built to endure. All the timbers are extra large and of clear spruce, so that loads have never had to be limited.

A railroad siding was also built at this time, with platforms for unloading four cars at once directly into the mill. Underneath the tracks further along coal pockets were constructed, to be filled directly from the cars by simply opening the hoppers and allowing the coal to run out.

Fire Strikes Again and Again

In 1904 the mill at Passumpsic, which did all the grinding for the store in St. Johnsbury, caught fire from the pulp mill, which was adjacent to the Ide mill, and the entire section burned to the ground. Again the miller was without a mill.

A mill was essential to keep the business going. To serve as a stopgap an old mill in Lyndon was purchased, overhauled and put into operation. No sooner had it begun to produce than it, too, caught fire and burned — this time from sparks thrown off by a passing locomotive.

Twice in the same year the company had been deprived, in a costly and discouraging way, of its most essential source of life.

A Mill That Meant Business

Many a strong business man would have said "enough'' at this stage of the game. But E. T. Ide was a determined man. Those who knew him had no doubt that even if the loss had been greater he would have started again. Moreover, it was a family business that had survived for nearly a hundred years and he had a tradition as well as his own pride to uphold.

The mill site and water power rights at Passumpsic were sold to The St. Johnsbury Electric Company for $15,000. Today this is but a fraction of the value of the property but at that time it was considered a handsome price. A contract was made with the Electric Company to furnish power for the new mill to be constructed in St. Johnsbury.

This new mill, fourth in the history of the business, was erected in 1905 adjacent to the new elevator built the year before. It was well built and stands today exactly as it stood when completed. The foundation is of thick cement on large piles driven 25 ft. to bed rock, since the soft filled-in land was not solid enough to support the building.

New machinery and equipment of the latest design were installed. Powered by electricity, this equipment included two roller mills, two attrition mills, two corn crackers, five stands of elevators, three bolting screens for sifting and grading meal, dust collectors, magnetic separators an automatic power shovel for unloading carloads of grain and a Fairbanks automatic receiving scale.

A Complete Plant

When this mill went into operation the company had a complete, well arranged and efficient plant, with a grinding capacity of 2000 bushels of grain per day and storage space for 30,000 bushels of bulk grain and 1000 tons of sacked feed, flour and other products. It provided the company with the facilities for further expansion an expansion that continued for many years.

A Reputation For Honor and Integrity

In addition to being a business builder E. T. Ide was a man of absolute honor and integrity. He established a reputation that is today an essential part of the business and an important factor in the continued customer loyalty which the company enjoys. He was active head of his family business for sixty-two years until his death in 1923 in his eighty-fourth year. For many years he was a leader in civic affairs, president of the Merchants National Bank in St. Johnsbury, and a member of the Board of Directors of the Vermont Mutual Fire Insurance Company in Montpelier.

He was a shrewd, aggressive man, with a faculty for looking ahead and the courage to back his plans with patience, hard work and money.

At the same time he was a family man of the old fashioned respected school. He raised six children, three sons and three daughters, on a balanced diet of discipline and kindness and left them a heritage of fond memories as well as a substantial business.

Of all the men who helped to build the business of E. T. & H. K. Ide Inc. few contributed more to its success than George M. Gray, son in-law of E. T. Ide.

He entered the business in 1888 and immediately began to prove his value. Likeable and energetic, he was a hard worker and a born salesman. Farmers from far and near wanted to trade with him. Always on the go and always selling, he sold where others could not sell and made friends wherever he went.

The secret of his selling success with farmers was that he was born on a farm and was always at heart a farmer. In addition to his duties as vice president and secretary, which offices he held for many years until his death in 1925, he owned and operated a large farm a few miles south of St. Johnsbury. Whatever he undertook he earned out with vigor, intensity and cheerfulness — qualities that made him an outstanding man in the community as well as a success in business.

A New Milling Generation

In 1900 William A. Ide, youngest son of E. T. Ide and present head of the company, went to work in the mill at Passumpsic.

He brought to his job a deep and abiding love of milling. Even before he entered the business he had familiarized himself with every phase of grist mill operation. By the time he was in his early twenties he had proved himself a capable miller and millwright with a thorough knowledge of mill construction, equipment and management. This knowledge has served him in good stead in building up the firm's physical plant through the years — just as his keen judgment and vision have been important in guiding the company's progress for the last three decades.

Few men have showed greater confidence in their sons than E. T. Ide showed in William A. Ide. From the beginning he gave him heavy responsibilities and throughout his life held high respect for his opinion in all important matters. This confidence and respect was returned, and for nearly a quarter of a century father and son worked together in close and mutually satisfying relationship.

Future Expansion

In 1909 the company leased and began to operate a mill in Bradford, Vermont, to meet the growing demand for feed and grain by the farmers in that prosperous section of the Connecticut Valley. This mill proved insufficient to meet these demands, so in 1914 a complete new mill was constructed in Fairlee, several miles to the south of Bradford and about forty miles south of St. Johnsbury.

This mill, built under the supervision of William A. Ide, was soundly constructed on modern lines and is today, after more than 38 years of service, still one of the most efficient units of us kind in northern New England. It is well equipped for grinding and mixing and has ample storage space for grain and sacked feed.

Meanwhile, more storage space was needed at St, Johnsbury. A new storehouse, a large L-shaped building adjoining the elevator building, was built in 1927. Built also under the careful eye of William A. Ide, it has two floors, the first of cement and the second of wood supported by heavy steel beams.

This completed the present plant of the Ide company, which provides space tor 35,000 bushels of bulk grain and 1500 tons of sacked feed, as well as capacity for mixing and grinding 3000 bushels of products each day.

Flood Takes A Toll

This new building had just been completed in 1927 when Vermont was hit by the worst flood in its history. It took a tragic toll of lives and property.

The water was six feet deep in the buildings on Bay Street. When it receded it left a heavy deposit of mud. The feed bags were piled twenty high. The lower five bags were soaked and immediately began to heat and steam. Men and trucks worked in shifts for days and nights until all the bags were removed and the building cleared. The loss was severe, uncovered by insurance.

The Business Today

Until recent years the E. T. & H. K. Ide business consisted of selling grain and feed unmixed to farmers, who mixed it to meet their own special needs or preferences. Today a great portion of the business is the manufacturing and selling of balanced animal and poultry feeds. These are mixed in the plant according to the most modern information available for various nutritional purposes. Five types of cattle rations, three poultry feeds, a pig feed, and horse feed are mixed daily. Grinding grain raised by farmers or "grist" has not changed through the years and farmers still bring their "grist" to Ide's, much of which is mixed with other grains to make up a balanced feed before returning to the farm.

Mixing is done in two modern mixers, each with a capacity of 1 1/2 tons. After mixing, the feed is elevated and run over a powerful magnet to remove all traces of metal. It is then run over a shaking screen to remove any foreign material. A recent addition to the plant equipment is a special molasses mixer with a capacity of 300 lbs. of mix per minute. Here the feed and molasses are mixed automatically after which the feed, ready for use by the customer, is bagged or spouted direct into trucks for delivery.

The Ide business today is a retail business. It does not attempt to compete with the large grain distributing companies on a wholesale basis. Accordingly, under the leadership of W. A. Ide, a number of branch stores have been established throughout the surrounding district within a radius of 50 miles. These branch stores are located at Fairlee, Passumpsic, Danville, North Danville and West Barnet. Each is managed by a man of wide acquaintance among the farmers of his district and a comprehensive knowledge of their requirements for animal feeds.

Among the farmers who buy their teed from the Ide Company are many whose fathers, and grandfathers were also customers of the company. It is a business that has earned such loyalty by adhering to the highest standards of quality in its products and maintaining a consistently high level of honesty and integrity in all of its associations with its customers. This reputation is one of its most important assets in building business among the farmers of the present generation.

Today, more and more responsibility in conducting the business is being assumed by Richard E. Ide, vice-president of the company, son of William A. Ide and like his forebears, Richard Ide has served a long period of apprenticeship in milling operations. His years of work for the Company were interrupted by two years’ service in the Army during World War II, one and a half years of which were spent with front line infantry in Germany. He is well qualified by both training and experience to assume lull leadership in the years to come.

DIRECTORS

- William A. Ide

- Mary Ide Gates

- Helen Gray Powell

- Paul A. Ide

- Theodore W. Sprague

- Elizabeth Ide Osborne

- James Everett Daniels

- Richard E. Ide

- Frederick G. Johnson

OFFICERS

- William A. Ide, President and Treasurer

- Richard E. Ide, Vice President

- Frederick G. Johnson, Secretary

- James Everett Daniels, Clerk

Men now deceased who spent practically all their working years with the Ide Company:

- Timothy Ide

- Jacob Ide

- Elmore T. Ide

- Horace K. Ide

- George M. Gray

- Frank W. Mason

- Charles Craig

- George E. Hall

Men now working for E. T. & H. K. Ide, Inc. who have been with the Company or many years:

| Years | |

|---|---|

| William A. Ide | 52 |

| Frank O. Lapoint (retired) | 50 |

| Otis B. Cutting | 39 |

| Pearl W. Blodgett | 37 |

| Bertram F. Allen | 35 |

| Alexander N. Berube | 35 |

| Frederick G. Johnson | 31 |

| J. Everett Daniels | 27 |

| Hugh W. Ramage | 26 |

| Raymond C. Locke, Sr. | 26 |

| Dewey S. Nichols | 25 |

| Richard E. Ide | 21 |

| Leslie I. Dwyer | 18 |

| Fred W. Wright | 18 |

| Frank O. Lapoint, Jr. | 17 |

| Wallace W. Mackay | 12 |

| Samuel I. Eastman | 11 |

| Benjamin C. Stanton | 11 |

| Maitland C. Bean | 10 |

At the present time there are approximately thirty men employed.

A booklet published in 1953 on the occasion of the company's 140th anniversary, it presents an idealized version of the business through the first five generations of leadership.

Published

12/17/2018

Updated2/20/2020